Mathematicians had puzzled about Euclid’s fifth postulate, also known as the parallel postulate, for hundreds of years. Around 1830, it became apparent to mathematicians that the fifth postulate is not always true.

Consider a straight line in a one-dimensional Euclidean geometry. Travelling along that line takes one progressively further away from the starting point. But what if an extra dimension is added? This was a concept that Euclid had not incorporated in his geometry. In two dimensions, for example, we can consider a circle as an example of a non-Euclidean “straight line” in “one dimension”. An observer travelling around the circle will eventually return to their starting point. This is not how the Euclidean one-dimensional geometry behaved.

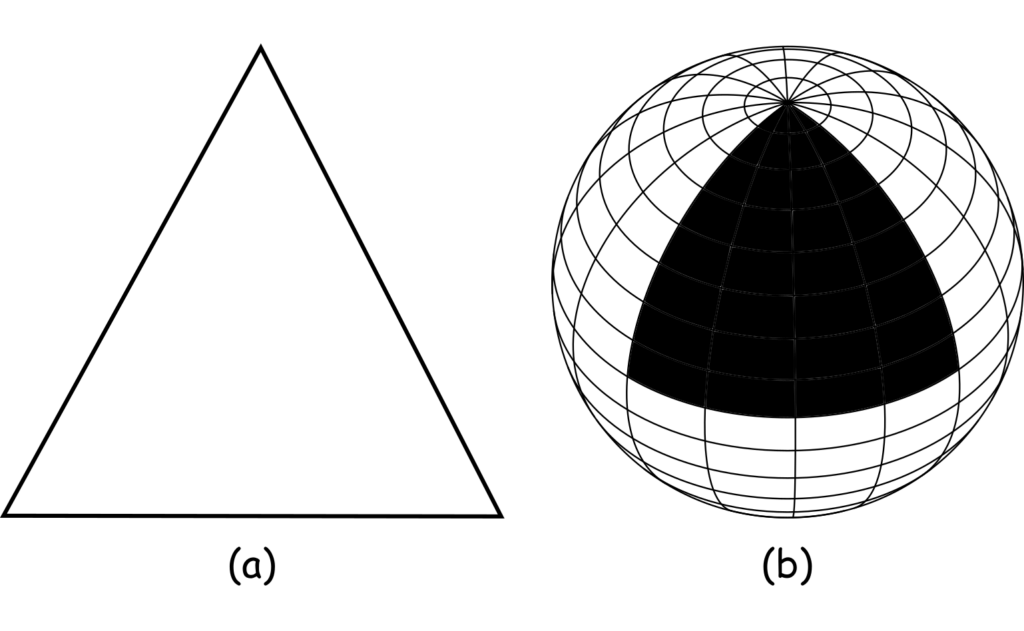

Now consider a Euclidean plane, with two coordinate axes applied to a flat surface. (In high school math class, this would correspond to a piece of notepaper on a desk.) Any triangle drawn on this surface will feature three internal angles that always add to 180 degrees (Refer Figure 5.1a). If we draw a circle, the ratio of the lengths of the diameter and the circumference is always about 3.14 (to two decimal places), a number known by the Greek character “pi” (π).

However, in non-Euclidean geometries, these axioms break down. For example, consider a non-Euclidean “two-dimensional” example. This incorporates an extra dimension to permit the deformation of the Euclidean geometry. In three dimensions we might consider that the flat plane is wrapped and stretched around a sphere such as a terrestrial globe. Note that adding the third-dimension results in deformation of the Euclidean surface in all dimensions, not just the third. The sphere curves in relation to each of the coordinate axes—the X-, Y- and Z-axes.

With this non-Euclidean geometry in place, we now return to our earlier example of the parallel lines. Imagine two people on the terrestrial globe’s equator several kilometers apart. If they both proceed due north, they are both travelling parallel to each other. However, if they continue long enough, they will meet at the North Pole. Therefore, in this scheme, separate parallel lines do meet, which invalidates Euclid’s fifth postulate.

| Figure 5.1: Euclidean (a) and non-Euclidean triangles (b) |

Next, consider a triangle drawn on this spherical surface (refer Figure 5.1b). Imagine two people standing at the North Pole. One of them proceeds due south, travelling down the prime meridian of zero degrees longitude, passing through Greenwich and stopping at the equator. The second person travels south by way of the 90th meridian West. Their southward path takes them through North America, until they also halt at the equator. If we consider these two paths as two sides of a non-Euclidean triangle, and the third side as the segment of the equator that joins the two people, we have a triangle whose internal angles add to 270 degrees. Each angle is a right angle (90 degrees), and the sum of the angles, 270 degrees, is different from the 180 degrees found in Euclidean geometry.

An objection might be that the two people are not really travelling in straight lines; the surface of the earth is curved. But we can address that problem. If we use a sphere twice the size of the Earth, then for a given distance, the amount of curvature is reduced. As the size of the sphere approaches infinity, the lines become straighter and straighter until they are in fact straight. Hence, by an appeal to infinity, we can straighten out the curved lines. Our “spherical” geometry describes a geometry with straight lines that conflict with Euclid’s fifth postulate.[1]

This non-Euclidean geometry also yields unexpected results for circles. Draw a large circle on the terrestrial globe. The diameter (or radius) of this circle bulges due to the curvature of the earth, and so is slightly longer than it would be in the corresponding flat surface Euclidean geometry (two-dimensional). There is “excess diameter” and “excess radius” compared with Euclidean geometry. If we were to use this geometry to calculate pi, the result would be less than 3.14.

To create a three-dimensional non-Euclidean geometry, we could add a fourth dimension to allow for the deformation of the three-dimensional Euclidean geometry. We will not provide examples, but it is worth pointing out that higher-level dimensions are mathematically possible—even if it is not clear how to visualize them. In fact, systems of dimensions higher than four also work mathematically.

In summary, we have described a non-Euclidean geometry in one and two dimensions and highlighted the possibility of three or more dimensions. We now know there is an infinite number of different non-Euclidean geometries. A two-dimensional non-Euclidean geometry does not need to be based on a convex spherical shape. It can also be concave in shape like a saddle.

Because there are an infinite number of possible geometries, Euclidean geometry is not to be termed “true” as such. Instead, it is simply one logically valid model of geometry amongst an infinite number of alternatives. However, at Newton’s time in history, it was still considered that Euclidean geometry exactly modeled the geometry of the real world.

[1] An alternate approach to “straighten” the lines is to make the observer and their field of view infinitesimally small.