In an irony of scientific history, the curtain closed on spontaneous generation at almost exactly the same time that Charles Darwin was putting the finishing touches on Origin, published in late November 1859.

Louis Pasteur, the brilliant French biochemist, began his well-known “swan-necked flask” experiments in 1859. By January 1860, Pasteur believed he had decisively disproven spontaneous generation but wanted to buttress his proof with more robust evidence to convince his most ardent opponents. That month, he wrote to his friend Charles Chappuis:

I am pursuing as best I can these studies on fermentation which are of great interest, connected as they are with the impenetrable mystery of Life and Death. I am hoping to mark a decisive step very soon by solving, without the least confusion, the celebrated question of spontaneous generation. Already I could speak, but I want to push my experiments yet further. There is so much obscurity, together with so much passion, on both sides, that I shall require the accuracy of an arithmetical problem to convince my opponents by my conclusions. I intend to attain even that.[1]

Pasteur presented his work on spontaneous generation to the Academie on February 6, 1860. He remarked in a letter to his father that his ideas “seemed to produce a great sensation”.[2]

In the summer of 1860, Pasteur continued his experiments in mountainous regions, to investigate his hunch that there are fewer airborne germs at higher altitudes. All his experiments pointed to the same conclusion—that spontaneous generation does not occur. Although some die-hard supporters of spontaneous generation continued to beat the drum for some time afterwards, it is generally accepted that by the early 1860s, Pasteur had disproved this ancient Greek presupposition. Pasteur himself stated that he had disproved the theory in his January 1860 letter cited above.

How does this line up with the timing of Darwin’s Origin? Darwin is believed to have formed his evolutionary ideas in the late 1830s, and then, for reasons which are hotly debated, delayed publication of his theory. It was only in 1858, when Alfred Russel Wallace sent Darwin the outline of a theory which mirrored Darwin’s, that Darwin was prompted to complete his text, and publish without further delay.

Although spontaneous generation was finally disproved by Pasteur in 1859–60, empirical evidence which counted against it was provided by Theodor Schwann in 1837, and by Schroeder and Dusch in 1854. But in an 1837 notebook, right around the time Schwann was publishing, Darwin noted that “[t]he intimate relationship between the vital phenomena with chemistry and its laws makes the idea of spontaneous generation conceivable”.[3] Darwin’s theory of evolution had roots which began in spontaneous generation, even if, during his long delay in publishing, spontaneous generation had become outmoded.

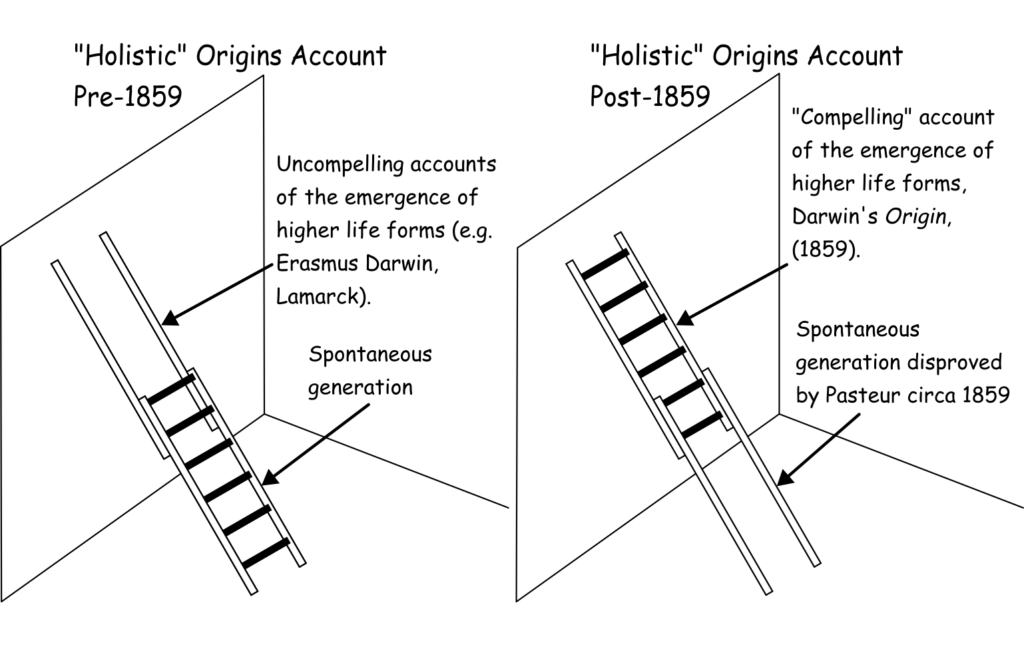

| Figure 5.2: Extension ladders representing naturalistic origins accounts, pre- and post-1859 |

But with Pasteur’s work, the ancient idea of spontaneous generation had been decisively overturned. This revolution came just as Darwin was publishing his theory—a theory which was built on the process that Pasteur had just disproved (refer Figure 5.2). The same types of revolution were observed when Newton’s laws of mechanics were radically overhauled by Einstein, and also in various technological advancements which made decisive breaks with the ancients.

The reader will recall that technology is an application of science. Therefore, if Darwin represented the capstone of an ancient template, we might expect to see similar examples of ancient technologies being overturned at the same time. And this is precisely what we do see. In the three areas of engineering we discuss below, ancient technologies were being perfected at around the same time Darwin published Origin, but then, Darwin-like, they were quickly overturned by technological revolutions.

The first concerns communications. In Esther 8:10, King Ahasuerus, also known as Xerxes (c. 518–465 BC), sent messages across his expansive empire via horse courier. Precisely the same mode of communication was used in America to connect the mid-west and California in 1860–61. The Pony Express, featuring legendary riders such as Buffalo Bill, transported letters to California in 10 days. It is true that the technology behind the telegraph had already been developed, but in the absence of an installed, operable system, the Americans of just 160 years ago relied on an ancient technology to deliver urgent messages.

Turning to the field of construction, we note that the world’s tallest building in 1859 was Strasbourg Cathedral, which used the same stone-on-stone construction method as the Pyramids and the Parthenon. Several other cathedrals, which were in various stages of completion, progressively took the title of world’s tallest building: the Church of St Nicholas, in Hamburg, in 1874; Rouen Cathedral in 1876, and Cologne Cathedral in 1880. But the Eiffel Tower, completed in 1889, presaged the emergence of tall wrought iron or steel-framed buildings. This construction method, which resulted in buildings known as skyscrapers, completely revolutionized the speed at which buildings were completed and their attainable height. The Empire State Building, with a roof height of 1250 feet, was well over double the height of the tallest cathedrals, and this immense building was completed in 1931 after a construction period of less than two years.

The third technological area is ocean-going transport. The age of sail commenced in antiquity. King Solomon maintained a fleet of ships (1 Kings 9) and the ancient Phoenicians were well-known for their seafaring prowess.

But the crowning achievement of the age of sail—the fastest ships of all—were the tea clippers. An early clipper, the Rainbow, was considered a revolution in naval architecture when it was built in 1845. Its performance in the water was in keeping with its sleek lines, easily outpacing all other ships then in service. (In fact, tea clippers may have been the only ships in history that could outpace the highway traffic of their era; the fastest transatlantic crossing by a clipper was completed at an average speed nearly twenty percent faster than a horse and carriage could average on a good road.) The most famous tea clipper, Cutty Sark, was launched in 1869 (which, incidentally, was ten years after the publication of Origin). Of course, a real revolution was in the offing; by the 1870s, steamships, which, unlike the tea clippers, could utilize the Suez Canal, were voyaging from China to Britain in just over 50 days. This slashed the 90–100 day period of the fastest tea clipper passages.

Both Newton’s and Darwin’s theories were like tea clippers—apparently revolutionary, they were actually the last and highest forms of ancient templates, all of which were about to be overrun by far larger revolutions. The notion that Darwin followed the template of the Greeks is widely accepted.[4] Edward Clodd, cited earlier, wrote Pioneers of Evolution From Thales to Huxley (1897),[5] and Henry Fairfield Osborn, Professor of Zoology at Columbia University, wrote From the Greeks to Darwin: An Outline of the Development of the Evolution Idea (1894).

But regarding timing, we can go further and say that Newton’s laws of gravitation and motion were like the Rainbow, which entered service decades before the Suez Canal opened and the steamships took over. In an analogous way, Newton’s laws, published in 1687, seemed assured, as non-Euclidean geometry was only discovered some 140 years later. Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, on the other hand, is analogous to the Cutty Sark, which launched in the same year that the Suez Canal made available a shortcut to steamships. Darwin published Origin at almost exactly the time when spontaneous generation was disproven.

[1] Vallery-Radot, 1920, p. 87.

[2] Ibid., p. 88.

[3] Peretó, Bada, & Lazcano, 2009.

[4] For an alternate view see: Zuiddam, Benno (2018) “Was evolution invented by Greek philosophers?”, Journal of Creation, 32(1):68–75.

[5] Thales of Miletus was an ancient Greek philosopher.